Speaking at Kololo Ceremonial Grounds on August 28, Kadaga said many delegates had received threatening messages and were being courted with gifts.

KAMPALA - The political season is now in full gear but will reach fever pitch when those aspiring to become Member of Parliament start campaigning on November 10, 2025, for the 2026 General Election.

However, in the theatre of Ugandan politics, political candidates face Shakespeare's Hamlet’s dilemma, except here, the choice is not between life and death, but between principle and profit, democracy and decay.

Every election cycle, politicians grapple with the calculus of voter bribery: To stuff envelopes with cash, hand out smartphones, or promise phantom favours, to win votes, or to stake their fate on the risky proposition that voters might actually choose leaders based on ideas, integrity, or a vision for the nation. The answer, too often, is clear.

In the run-up to the 2026 General Election campaigns, which included party primaries, transactional politics reared its ugly head. It is likely to continue when the season gains momentum after the nomination of all politicians.

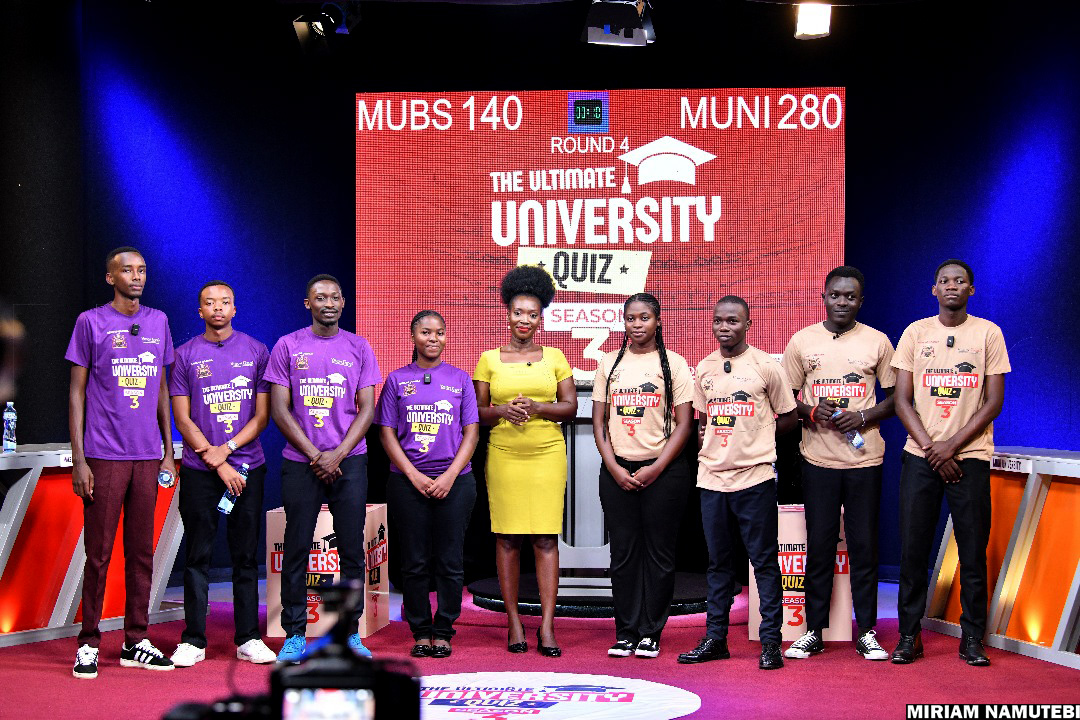

Former Speaker of Parliament Rebecca Kadaga echoed these concerns during the recent National Resistance Movement primaries.

Speaking at Kololo Ceremonial Grounds on August 28, Kadaga said many delegates had received threatening messages and were being courted with gifts.

Experts and civil society groups warn that paying for votes fundamentally undermines the democratic process. They say when the focus shifts from candidates’ vision and governance competence to immediate material gain, accountability suffers.

According to analysts, vote buying entrenches a cycle of corruption. Issues like health, education, and job creation are often sidelined in favour of transactional politics.

According to Marion Agaba of Anti-Corruption Coalition Uganda, elections have morphed from contests of ideas into auctions of influence, where the winner is not the most qualified but the wealthiest bidder.

He says leaders enter office shackled by debt, their agendas hijacked by paymasters, and their constituents left with empty promises.

“When you sell your vote for sh5,000,” Agaba says, “don’t weep when your Member of Parliament (MP) sells their soul to a contractor.”

This dilemma is a vicious cycle as Francis Kibirige of Afrobarometer says: 60% of Ugandans decry bribery, yet 35% admit taking handouts. For many in poverty, a bribe is survival; for politicians, it’s the only playbook they know.

However, according to seasoned lawyer Peter Walubiri, this is not a legal problem but political sickness.

“Elections are now private businesses, and the ballot is for sale,” he states.

Agaba states that Ugandans are now not getting the best leaders because the citizens have high expectations for quality services when they are underserved.

The solution

Agaba emphasises that Ugandans have constitutional rights and responsibilities in choosing leaders who serve their interests.

He cautions that if citizens ‘sell their rights’ for short-term gains, officials exploit their positions for personal gains.

Agaba urges cohesive voting driven by ideas, not transactional exchanges. He highlights the need for politicians to focus on substantive policies rather than electoral wins.

He says addressing political financing is crucial and that it burdens both politicians and the nation, urging parties to deliberate on responsible spending.

Agaba referenced Uganda’s 2001 era, saying politics cantred on ideas and national progress, contrasting with today’s challenges.

Francis Kibirige, the Afrobarometer’s Uganda national coordinator, highlighted the complex issue of vote buying, noting that what some call ‘bribery’ others might view as ‘facilitation.’

According to Afrobarometer’s 2021 election study, 35% of Ugandan voters reported receiving money to vote for candidates, with incumbents reportedly offering more than the challengers.

Kibirige noted a contrast in perceptions: while 60% of Ugandans consider bribing voters wrong, there's a nuanced view where offering bribes is seen as bad but receiving them is not necessarily viewed similarly.

He pointed out transactional dynamics extend beyond elections, citing government jobs often involving bribes, leading to a cycle where Ugandans might accept money to recoup costs.

He illustrated challenges in political processes like NRM primaries, where voters might struggle to support candidates not offering financial incentives, potentially leading some to disengage.

Kibirige observed that Ugandan voters often do not press candidates on policy promises.

He added that 75% of voters believe politicians prioritise personal interests over public needs and often pledge unfeasible actions, fostering perceptions of dishonesty.

James Ereemye Mawanda, spokesperson for Uganda's Judiciary, emphasised that following the general elections, the courts are prepared to handle cases of voter bribery should the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) decide to prosecute alleged offenders.

“If the cases are brought before the courts of law, we are ready to handle it,” Mawanda said.

He noted that if culprits are proven guilty, they will face punishment under the law, and in civil courts, this could lead to declarations including nullification of elections.

Mawanda attributed the prevalence of voter bribery in Uganda to lawlessness, stressing that the law clearly outlines criminal acts.

He urged voters and politicians to respect the rule of law, understanding what is permissible and what constitutes an offence, to foster credible electoral processes.

On September 24, this year, the Judiciary launched an electoral guide, aimed at helping judges to handle election-related disputes.

Titled “Enhancing Electoral Justice in Uganda: A Review of the Court of Appeal Decisions Arising from the 2021 Parliamentary Elections,” the guide focuses on rulings from the Court of Appeal, the final arbiter for parliamentary and local council election disputes.

City lawyer Elison Karuhanga said that voter bribery is rampant in Uganda due to the growing commercialisation of politics.

He stresses that effective enforcement of existing laws against voter bribery is crucial to tackling the issue.

Karuhanga noted that bribery is outlawed, and it operates to deny the free will of the voters as their choice is determined by the enticements given and received.

Peter Walubiri, a seasoned lawyer, posits that voter bribery in Uganda stems from a deeply ingrained political issue rather than a legal problem.

He argues that bribery is symptomatic of widespread corruption, where politics has become commercialised from the top echelons down.

Walubiri said that the commercialisation leads to parliamentarians being incentivised to alter constitutional provisions or approve specific budgetary aspects, often swayed by government or private interests.

The lawyer notes that the transactional political culture fosters an environment where voters perceive elected officials, including members of parliament and local government leaders as prioritising personal financial gain over public service delivery.

“The entire political structure revolves around exchanges of money, jobs, and services,” he observes.

Walubiri underscores that the entrenched political paradigm renders laws against bribery ineffective, asserting that Uganda’s anti-bribery legislation cannot yield results without a fundamental transformation of the country’s political and economic fabric.

“Unless you overhaul the entire political and economic system, you cannot outlaw voter bribery,” he emphasised.

According to Walubiri, voter bribery has escalated over time, citing that parliamentary candidates in Uganda's 2021 elections spent approximately sh500m.

He stressed that dismantling the culture necessitates a profound overhaul of a political system entrenched in corruption, commercialisation, militarism, and violence, a change he believes transcends legal reforms.

Enock Nyongore, Nakaseke North County MP, attributes the prevalence of voter bribery to a culture of lawlessness, stating that individuals feel emboldened to engage in such practices knowing they face little to no consequences.

If someone believes they can act with impunity without being sanctioned, it's a recipe for disaster,” he notes.

Nyongore criticises the commercialisation of politics, likening elections to private business ventures, and advocates for strict regulations to curb the trend.

He pointed out that voter bribery was evident in the National Resistance Movement primaries, mirroring patterns seen in general elections.

Nyongore urges a shift towards integrity and moral uprightness, moving beyond mere ‘educational collections’ and embracing a more principled approach to politics.

Amos Semakula, a registered voter from Nakawa Division in Kampala district, highlights poverty as a driving factor behind voters accepting bribes from politicians.

“Many Ugandans struggle to make ends meet, so when opportunities to earn money arise, they often seize them, even if it means compromising their voting decisions,” he said.

The Uganda National Household Survey indicated that between 2019/20 and 2023/24, Uganda’s national poverty rate declined from 20.3% to 16.1%. This reflected growing trust in commercial farming, education, and inclusive models like the Parish Development Model.

Karamoja’s poverty rate was at 74.2%, while Bukedi and Teso also lagged behind.

Michael Odeng

Michael Odeng